Snow in Haiti and Thoughts on Teaching

No, it’s not actually snowing in Haiti: we learned weather and seasons in our English/Creole class yesterday, and Kelly and I were surprised to find out that there is, in fact, a word for snow in the Creole language. But I bet the title made you want to keep reading 😉

As I finish my second full week of teaching here at St. Barthelemy, I thought I’d reflect on some of the challenges Kelly and I have faced and how we’ve tried to overcome them. I’m optimistic about our work at the school, and I hope that my blogs so far have conveyed this outlook, but I definitely don’t want to give the impression that teaching kids is all fun and games. It’s been really enjoyable at times, but also very difficult at times. A few lessons I’ve learned so far:

Teaching is hard.

I feel like I have a whole new appreciation for every teacher I’ve ever had. Standing in front of a room full of students and trying to get across an idea verbally or visually is quite daunting, especially for someone like me who’s more of a behind-the-scenes kind of person. It’s one thing to understand a concept that you’ve known for years, but to explain it to a room full of kids who’ve never heard of the concept is completely different.

Teaching in a different language is even harder.

Not only do we have to teach health and science concepts to the students, but our translator, who is a native Terrier Rougian (not quite sure how to say that?), is not familiar with a lot of the concepts either. Before class, we have to make sure that he understands the concepts well enough to translate the ideas and related vocabulary. I’ve learned to avoid jargon-y phrases like “made up of cells” and use more easily translatable phrases like “composed of cells,” or use “eliminate germs” instead of “get rid of germs.”

I’m also learning that many words just don’t translate from English to Creole. In the 3rd grade class the other day, we discussed red blood cells and their ability to transport oxygen. The teacher asked a question about “glob rouge,” and my college-educated mind jumped to the word “hemoglobin,” and for a minute I was really excited to talk about heme groups and iron and all of that nerdy stuff… and then I realized that he probably just meant “red blood cells.” I don’t think the term “hemoglobin” actually exists in the Creole language.

Teaching requires a level of energy that is nearly impossible at 8 am.

(For those of you who’ve dealt with me in the morning, you can imagine how particularly difficult this is for me!)

Even though we’re speaking in English and the students have no idea what we’re saying, we still have to sound enthusiastic about the lesson. And one thing that all kids have in common, regardless of nationality or age, is that monotone lecturing will lose their attention in less than 5 seconds. So we try to sound as excited as humanly possible about water purification and hand washing.

By the way, Kelly is a saint for being so chipper during the English lessons. After several hours with hundreds of kids, I just don’t have it in me to get as excited about greetings and numbers as I do about cells.

Students tend to take things very literally.

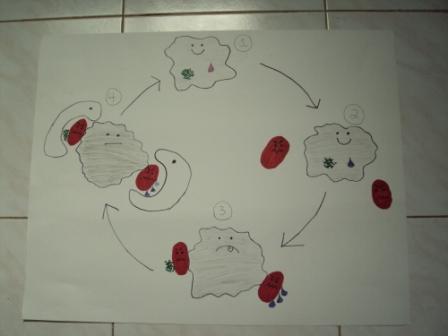

When we tried to explain how germs take water and nutrients from our body, we used a water bottle and mango to represent the body’s water and nutrients. The 6th graders, however, only saw a water bottle and mango, and they thought we were trying to show how to wash fruit before eating it. The next time we taught the 6th grade, we made a diagram (see below) showing a microbe taking a cell’s water (drawn as a water drop) and nutrients (drawn as green dots). I considered drawing a banana or bread inside the cell to represent nutrients, but Kelly pointed out that we’d then have a bunch of 6th graders who think there are bananas and bread in cells…. bad idea.

Basic science concepts are fun!

By far, our best lesson yet was the cell lesson we taught the 4th, 5th, and 6th graders this week. When we explained the different kinds of cells (see Kelly’s post for details), it was kind of like describing different characters in a story, each with their own roles and personalities. When we explained how white blood cells attack invading microbes, it was very convenient that leukocytes really do eat foreign bodies (see my Pac man-like drawing above). When we explained that some neurons in our body can be up to one meter long, our translator told the class that we exaggerate a little, but we corrected him and emphatically said that it’s true. Forget fairy tales and monsters—cells are just as cool! So I’m learning that science topics, especially concerning the human body, can be really interesting if taught in a narrative fashion.

Limited resources make not only teaching, but learning, even more difficult.

As a product of American education, I’m beginning to realize just how spoiled I’ve been for the past 18 years. I learned with play-doh, coloring books, educational CD-ROMs, and Sesame Street. Kids in Haiti learn with… chalk, one notebook, and a few posters around their classrooms. The fact that St. Barthelemy teachers are able to teach their lessons with such limited resources, and that the students try so hard to learn with only a chalkboard and their own imagination, absolutely amazes me.

The weekend before I came to Haiti, I was visiting family in Nashville, and my aunt showed us around the exhibits in the Nashville Science Center to which she contributed (hi Aunt Tina!). One of exhibits, Body World, had a huge, beating heart to show how the circulatory system works, and a larger-than-life set of lungs to show how the respiratory system works. I can’t even imagine how much the kids at St. Barthelemy would love to see such an exhibit and how much it would improve our health lessons.